The Only White

About

Mid-winter 1964, a phone rings at Johannesburg Railway Station. John Harris speaks quickly into the receiver: “This is the African Resistance Movement. We have planted a bomb, It is not our intention to harm anyone. Clear the Concourse.”

They don’t..

The bomb explodes, twenty-three are injured, one dies.

Does the end justify the means? Does one life matter?

The Only White is a true retelling of a story in a desperate fight for freedom, a story of the one white man executed for political activities in Apartheid South Africa. But it is also a story of love and courage and comradeship, and love.Written by Gail Louw, multi-award winning playwright, with plays performed throughout the world.

Praise for this book

The Only White at Chelsea Theatre

By Elisabeth Beer / April 9, 2023

This play telling the true story of John Harris’ (Edmund Sage-Green) incarceration and execution in 1965 South Africa is appropriately titled The Only White – because he is the only white person ever executed in the country’s history. It is told mainly through conversations within the Hain family who are taking in John’s wife. In The Only White, most of the time two scenes are being viewed – John is in his cell and the family with Anne Harris (Avena Mansergh-Wallace) at the home. The Hain family who are close friends of the couple and fellow activists consists of Wal (Robert Blackwood), Ad (Emma Wilkinson-Wright), and their 14-year-old son Peter (Gil Sidaway). As the family goes about the best ways to help John, he is shown trying to withstand his days in his cell. He is beaten and suffering greatly. But John is heard from only briefly. So, the narrative is largely developed by conversations in the Hain family’s living room, and sometimes their garden to avoid possible government eavesdropping.Edmund Sage-Green and Avena Mansergh-Wallace.

Edmund Sage-Green and Avena Mansergh-Wallace.

This perspective allows for discussion to occur about John’s accused crime. Both parents are activists who take that aspect of themselves seriously. And their son Peter is curious and consistently wants to be more involved. He looks up to John as a mentor. And throughout the show, his thinking is left without cynicism and his father participates in many intense conversations where Peter is helped to realize the grim complex reality of the situation. His youth leads him to point out obvious statements that the adults can find rebuttals for but are still worth considering. There is no consensus reached within the household about the true morality of John’s actions which I think is important. It begs the question: is violence ever necessary?Once John Harris is faced with the damning testimony by his friend and fellow imprisoned ARM member, John Lloyd, his fate is sealed. Attempts are still made to save John from hanging, but it is soon clear that his skin color won’t save him as all predicted. And now discussion occurs within the Hain home about John Lloyd’s morality. Within each discussion in the family’s living room, Wal acts as the voice of reason and moderator while Peter is asking the questions and reacting to what is all so terrible and confusing for any 14-year-old to comprehend. This dynamic is very useful to the audience. It allows the complexities of the issue to be easily digested.

The Only White is heartbreaking and beautiful, the direction and dialogue make the show entertaining and intriguing instead of a documentary – thanks to director Anthony Shrubsall and playwright Gail Louw. I came into the show knowing nothing about the event and was able to catch on after the intermission and some light Googling, but found myself enamored by the story after I left the theatre. This is a relatively recent event and many people involved are still alive. I found myself reading multiple articles about many who were involved. The portrayal of them as characters in a play drove me to learn more about them as people. Which I think should be seen as an achievement for the creative team. If you want to understand the events in the play, I do suggest refreshing yourself on the Johannesburg Railway Station Bombing and the execution of John Harris before attending. But if you are slightly or completely unfamiliar with the background, this play will intrigue you and you’ll find yourself learning quite a bit of history while being entertained.

4 stars

Review by Elisabeth BeerMid-winter 1964, a phone rings at Johannesburg Railway Station. John Harris speaks quickly into the receiver: “This is the African Resistance Movement. We have planted a bomb, It is not our intention to harm anyone. Clear the Concourse.”

They don’t..

The bomb explodes, twenty-three are injured, one dies.

Does the end justify the means? Does one life matter?

The Only White is a true retelling of a story in a desperate fight for freedom, a story of the one white man executed for political activities in Apartheid South Africa. But it is also a story of love and courage and comradeship, and love.

Highly Recommended Show

South Africa, 1964. A bomb explodes at Johannesburg Rail Station; despite repeat warnings the concourse isn’t cleared and a woman dies. A 14-year-old Peter Hain, future activist and Labour minister, is at the heart of this drama. Gail Louw’s The Only White, directed by Anthony Shrubsall, opens at Chelsea Theatre till April 22nd.

Louw’s acclaimed for her probing plays on politics – The Ice-Cream Boys at Jermyn Street covered recent South African politics; Blonde Poison, Nazi collaboration; A Life Twice Given, the outfalls of cloning. She’s also known for brilliantly off-kilter explorations of the same themes through wholly different premises: Clone consequences in a psychiatrist handling a proto-Trump shooter for instance in Storming; Germanness through a man inhabiting Brahms in Being Brahms; witness against hierarchy in Shackleton’s Carpenter (also Jermyn Street); sexual abuse in The Good Dad.

The Only White like The Ice-Cream Boys is a scrupulous, fascinating and wrenching drama in Louw’s realist mode, examining one white, nominally privileged family’s resistance to Apartheid. Focus remains exclusively on them to highlight yet another side of the way an obscene racism impacts those who refuse to collaborate with their own privilege.

Using source materials with active permission of surviving relatives, Louw’s recreated the sheer oppressiveness of a regime that punishes white liberals, proscribing free speech and even banning them from speaking to anyone else. So liberals resort to at first peaceful then more militant tactics. How far do you go? The ANC, operating en masse from abroad as Wal (Robert Blackwood) points out, are effective. Lone liberals blowing up pylons get nowhere. The authorities blank sabotage from the news. Power-cut: nothing to see here.

So if you plant a very public bomb and it explodes, that’s no power cut. Warn everyone so only the concourse gets hurt. But what if the authorities blank again, this time to ensure someone dies?

It’s a world known with bitter intimacy by the Hain family – the surname isn’t mentioned; despite verbatim and biographical elements, these characters might suggest a universal South African liberal family. Activists Ad (Emma Wilkinson-Knight) her husband Wal, son Peter Paul (Gil Sidaway), their married younger friends Ann (Avena Mansegh-Wallace) and John Harris (Edmund Sage-Green) are one nucleus of an extended family of either exiled or arrested liberals.

John’s the last of his activist ARM group: the buck stops with him. When it comes to getting messages out only Wal’s left, smuggling Al’s ingenious notes in Thermos flask linings, hollowed oranges, cakes, unspeakably stained handkerchiefs that nevertheless are written all over in invisible ink. And there’s what to do with boiled expanded onions. The sheer inventiveness of these homely intellectuals matches anything in the French resistance.

The authorities inadvertently threaten that too. One bitter joke revolves around how Wal like Ad earlier, is now proscribed and can’t even watch his son’s cricket match. But by special dispensation they’re allowed to talk to each other! So who’s left to carry messages?

And when John’s arrested for murder, who really knew his plans, who thought he’d carry out his friends’ wishes, and were they more extreme than he? And when one is called upon as trial witness, what will they say in his defence? How far will the authorities press?

Louw grew up in South Africa. Her masterly play probes the details of state oppression and its influence, how differently liberals react under sanction, blackmail, torture. Early on John has his jaw broken. There’s plots, state counter-plots immediately intercepted but dealt with creatively. Fallout on family and friends is incremental, then overwhelming. But this is a story of “we shall overcome” as is finally sung; their heroism a matter of record. It should leave you in jaw-dropped awe.

That bomb’s front and centre. John’s been arrested. Languishing in Malena Arcucci’s striking set of a central cage whilst the period 1964 living room foregrounds it, the horseshoe stage admits of a strained intimacy: a site of two chairs, an authentic 1960s coffee table and orange rugs, Peter Paul sometimes sprawled across thumbing a book. It’s a singular concise conceit. At an opposite diagonal a small garden with tendrils makes too-brief use of solitary communings with grief, and a letter. Arcucci’s costumes too source period clothing – slacks (orange again, in Wilkinson-Wright’s second-act change) and a splendid early 1960s eggshell suit for Ann.

Chuma Emembolu’s sound is effective from that shattering crump and period music, as well as idiomatic telephone voices (Bu Kunene’s quietly outraged lawyer Ruth Heymann, Blackwood’s sinister police officer Du Toit). Lighting though lacks differentiation and means the generally tenebrous living room hardly shifts when the soft spotlighting falls on the central cage. It needs re-jigging.

Wilkinson-Wright’s Ad is a beautifully-wrought, thinking creation. You sense immediate alarm, suppressed so just we see a moment before the other characters register it. Her modulated English-South-African voicing is shared by Blackwood – there’s a whole spectrum of Anglophone accentuals shading towards Afrikaans guttural; these are the more British sort. He also gets voice and that phlegmatic liberal assurance struck through with the real alarm he’s suppressing. Wilkinson-Wright in particular moves with an agency meaning you don’t take your eyes off her when she suppresses news, delves into an orange to demonstrate subterfuge, or desperate reassurance in a hug.

Blackwood’s affect is mainly vocal. Less mobile, more planted than Wilkinson-Wright, ultimately conveying a man less certain of emotionally the right thing to do than argue it, his moments of release are palpable: a cricket-catch game with Peter Paul and ultimately Ad, suddenly forestalled.

Mansegh-Wallace’s Ann is a study in buttoned-up anxious liberalism. Letters from her incarcerated husband John seem florid, slightly antiquated to us now, but they’re authentic, and however awkward the voicings of a man who recognises early second-wave feminism, but still praises Ann as “the best wife” which she takes with pride. It’s also how Mansegh-Wallace’s Ann seems to have been built up. Her character’s purposefully stiff, costumes designed to literally button her up. An earnestness that can suffuse the production (not play) seems to breathe from her character, even when disguised.

Sage-Green’s compass is limited and he takes one striking moment to elevate John, a beautifully directed moment at the end when a hitherto-unused part of the stage and exit is deployed. It’s a tricky part since John’s roller-coaster emotions are unpredictable and Sage-Green navigates John’s mix of emotions with portraying glum stoicism, rare shafts of joy and slightly melodramatic gestures.

Sidaway’s prematurely adult Peter Paul is a neat if sotto voce study in adolescent dreams (James Bond rescue plans) with sudden ice-cold maturity, volunteering for very real dangers. His – and Blackwood’s – finest moments come with a tender Wal, knowing his son will follow him and grow fast but is still 14.

Shrubsall makes fine use of spatial polarities in this production and the whole theatre’s used: it really expands the play. The production will pick up pace too, shake off its early earnestness, and tonal dialectics that might benefit from preoccupation, occasional subtext. Because Louw’s play and some of Shrubsall’s direction can show this gloriously – and overtly point up moments of joy – the cricket-ball, Sidaway’s whoop of rugby-tackle-lore, and a family life that’s waiting to be inhabited just a touch more in that attractive room, lapped by terror.

You might have caught a Radio 4 Today interview with Peter Hain at 8.45 on the 6th April, now available on BBC Sounds: It underlines why this is a vital drama that needs to seen – and possibly heard on radio too. See it here and subsequently a well-deserved transfer or revival.

Published April 7, 2023 by Simon Jenner

4*

Gail Louw’s The Only White is an intense and moving portrait of a family and friends riven by grief and anger as they come to terms with a loved one’s turn to violence in pursuit of political ideals in apartheid South Africa.

The play tells the true story of John Harris (played by Edmund Sage-green), a political activist in the 1960s who became the only white person executed in apartheid South Africa. John planted a bomb at a train station in Johannesburg that exploded and unintentionally wounded 23 people and killed one. Despite John’s warnings, the authorities did nothing to evacuate commuters, setting off suspicions that the government used the bombing as cover to target activists.

It revisits the period during his incarceration and subsequent execution and takes the audience into the private spaces of those fighting for John’s life and lays bare all their emotional turmoil. The set merges the Hain family (friends of John) living room and John’s prison cell into one space and plays the contrasts of one another. It is particularly profound to watch the family in their living room plan to save their friend, all the while John quietly whimpers (after being tortured) in the background on the concrete floor of his prison cell.

It asks difficult questions about the use of violence as a means to pursue political ideals, how law became arbitrary in the hands of vicious bureaucrats who procured justice through violence and terror.

One can almost feel the helplessness of John’s wife (played by Avena Mansegh) and the Hain family (played by Gil Sidaway, Robert Blackwood, and Emma Wilkinson Wright) as they stand at the mercy of the apartheid government, which now controls John’s fate absolutely. One can almost taste the bitterness of naive idealism ground down by political reality.

Most profoundly though, The Only White, bears witness to one of apartheid’s most insidious effects — the unravelling and breakdown of a human being in an unjust society.

It runs until 22 April.

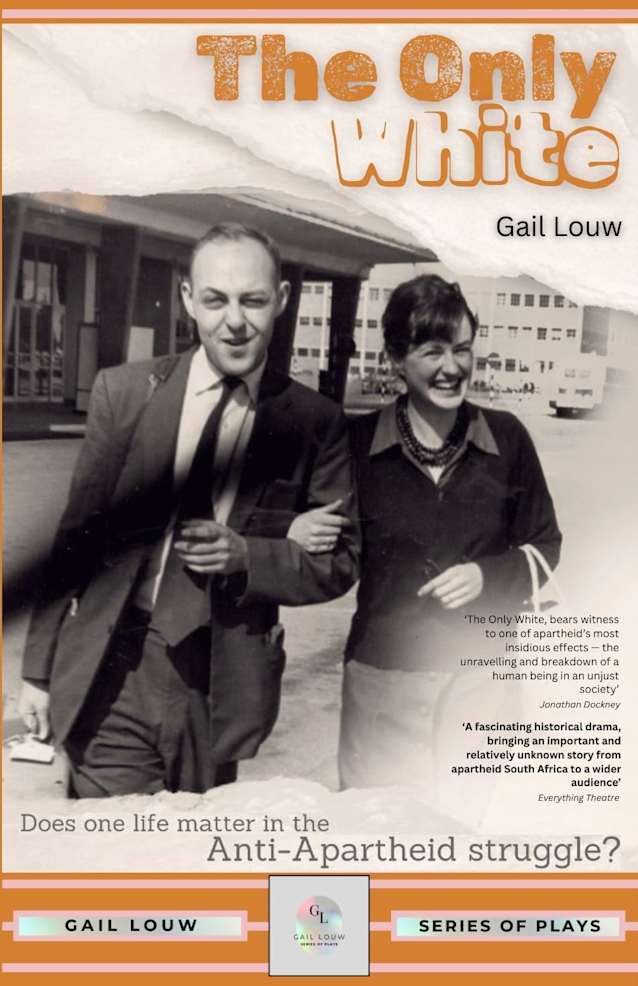

A play in London about the only White political activist to be hanged for his part in the resistance to South Africa’s apartheid regime (John White, pictured above) stirs up deep emotions for Peter Hain, who recalls his family’s involvement in the struggle.

It was quite something viewing a cathartic event 60 years ago from my South African childhood re-enacted in a stunning new play, The Only White.

Written by Gail Louw and performed brilliantly in April at Chelsea Theatre, London, it took us back to 24 July 1964 when a bomb exploded on the Whites-only concourse of Johannesburg’s main railway station.

I still remember, aged 14, hearing the news on my bedroom radio in Pretoria and rushing to seek reassurance from my anti-apartheid parents, not imagining for a moment that they would be involved but needing to hear them say so.

A few days later, Ann Harris, with her six-week-old son David, turned up unexpectedly at our front door from her home in Johannesburg, explaining that her husband John had been arrested and was being held in Pretoria local prison.

Both were teachers, close family friends and fellow activists in the Liberal Party – by then the only legal anti-apartheid group, Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress and other groups having been banned, their leaders on Robben Island or locked up elsewhere.

Ann was distraught, explaining how she had been refused permission to see John. But she had been told that she could bring food for him each day and collect his laundry.

Mom and Dad, with typical generosity, suggested that she stay with us until his release.

They assumed that John, who had been under police surveillance after being issued with a banning order months before, could not possibly have been involved in the station bombing and would be released in a week or so.

Ann and baby David moved in. But, instead of a short stay, they were with us for nearly 18 months and became part of the family.

Then, a month after the explosion, came the news that an elderly woman sitting nearby had died and John Harris was charged with murder.

Ann had admitted to my parents what she had known all along: that John was indeed responsible for the bombing.

Warning ignored

Although Mom and Dad were upset and condemned without qualification what John had done, they remained convinced that he never intended to harm anybody. He had meant it as a spectacular demonstration of resistance to tightening state oppression.Indeed, as confirmed in evidence at his trial, he had telephoned a 15-minute warning to both the police and two newspapers, urging that the station concourse be cleared. But the warning was ignored.

Two decades later, it emerged that the decision not to use the station loudspeaker system to clear travellers from the concourse had gone up through the notorious head of the Bureau of State Security (BOSS), Hendrik van den Bergh, to the justice minister, John Vorster.

John Harris was a member of the African Resistance Movement (ARM), with other close friends in the Liberal Party, who felt that non-violent means had reached the end of the road and that the sabotage of installations such as power pylons was the only way forward.

My parents had themselves been confidentially sounded out to join the movement. But, quite apart from the serious moral questions raised by violence, Mom and Dad considered such action naive and counterproductive, believing it would simply invite even greater state repression without achieving anything tangible.

John Harris’s trial opened on 21 September 1964 in the same Pretoria Supreme Court chamber as, a year before, Nelson Mandela and his underground leadership comrades had been sentenced to life imprisonment.

At the outset came a terrible blow: John’s station bomb co-conspirator, John Lloyd – another family friend and Liberal Party member – was to be the main prosecution witness.

Lloyd did not merely give evidence in corroboration of John’s own confession (which would have carried a life sentence for manslaughter), but, damningly, went much further, insisting that John’s act was premeditated murder. The consequences were to be fatal, for the judge accepted Lloyd’s version.

However, Lloyd (the flatmate of fellow ARM member and friend Hugh Lewin, who had been arrested on 9 July) had been detained on 23 July, the day before John carried out his part of their project. It was not established whether the security services thereby had advance notice of the station bomb, but Lloyd’s initial statement to the police mentioning John Harris, and the plan to plant a bomb at a station, was made at 12.45pm on 24 July, nearly four hours before the explosion.

It may therefore have been that the security services had even greater forewarning than John himself gave by telephone. If so, like the decision to ignore that warning, it suited their purposes to allow the bomb to explode as an excuse for the clampdown that followed.

Sentencing him to be hung, the judge stated that Lloyd’s evidence proved incontrovertibly that John indeed had ‘an intention to kill’ and so was guilty of murder.

Lloyd was released as part of an immunity deal, by which he avoided being charged as an accomplice, and flew to London with his mother, refusing repeated pleas to retract his ‘intention to kill’ evidence – and years later presenting himself as an anti-apartheid hero to the citizens of Exeter where he’d become a practising solicitor.

Just before 5am on 1 April 1965, John Harris ascended the 52 concrete steps to the pre-execution room next to the gallows at Pretoria Central Prison to face the grisly, medieval ritual of being hanged by the neck until dead.

He was singing ‘We Shall Overcome’ when the hangman checked all was ready and pulled the lever, plummeting him through huge trapdoors.

Silent tribute

Fourteen hundred kilometres to the south, on Robben Island, Nelson Mandela and his fellow political prisoners, gruellingly digging limestone from the quarry, paused to stand and observe a minute’s silence ‘for a great freedom fighter’, the only White political activist to be hung – over one hundred blacks were.The station bomb triggered a frenzy. Never before had Whites been attacked in this way. As my Dad had prophesied, the security services were quick to exploit the resulting panic. The bomb gave the apartheid government exactly the pretext they wanted to enforce an even more oppressive regime, and systematically to discredit and destroy the Liberal Party, which became illegal a few years later.

Having long been targets of the Pretoria security forces, my parents were now the principal targets of the whole state and its compliant media. Instead of being one of many enemies, it was almost as if we were the enemy,

In September 1964, my Dad was handed a banning order with a special clause inserted giving him exceptional permission to communicate with his wife – for my Mom had been banned a year before. As a married couple, they had to be given an Orwellian exemption from the normal stipulation that banned persons were not allowed to communicate in any way.

Then Dad’s employment as an architect specialising in hospital-laboratory design was blocked by the apartheid government, and our family was forced to travel to exile in England.

Steaming out of Cape Town on an ocean liner in March 1965, I remember looking out over the deck railings, feeling queasy as the ship heaved heavily in the Cape rollers, and glimpsing Robben Island, grim behind the cold spray, imagining how Nelson Mandela was surviving in his bleak cell, where he was then into the third of his long 27 years in prison.

The Only White dramatically brought all that trauma back – and as for witnessing actors playing my late parents and my 14-year-old self, that was a real emotional rollercoaster.

Lord Hain’s memoir A Pretoria Boy: South Africa’s ‘Public Enemy Number One’ was published in Africa by Jonathan Ball, and in the UK by Icon.